In one of my earlier posts on reading Gregorian chant I promised to discuss staves and clefs later on. They’re a little different in Gregorian.

In one of my earlier posts on reading Gregorian chant I promised to discuss staves and clefs later on. They’re a little different in Gregorian.

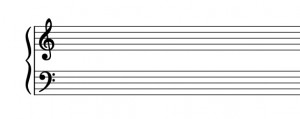

Modern music notation uses five lines, like this:

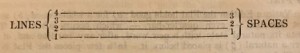

Gregorian chant, in contrast, uses four lines:

The range of Gregorian chant doesn’t usually go beyond an octave, so you won’t see two sets of musical staves together, as in the first example.

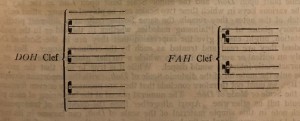

Gregorian uses “moveable clefs”, that is, that Doh or C can start one of three lines and Fah or F can start on one of two.

The purpose of this is to permit melodies of different ranges to appear on the staff.

It’s important to note that in singing Gregorian chant, what we think of as “C” in modern terms, that is the middle C on a well-tuned piano with reference pitch to modern A=440, is not likely to be the case. Instead, “C” will be whatever the schola singers or the singing monk or nun finds is most natural and comfortable for their voice. All other notes will then be in relation to that note. (The same likewise for “F”).

So if you have a wire harp like mine, which is tuned to a pitch reference other than A=440, to prevent string breakage, then you’ll be playing Medieval sacred music which is not concert pitch. And that’s fine!

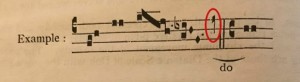

Next up we have the custos, or guide. This little flag that appears at the end of a section or phrase (there are no measures in Gregorian chant) indicates the upcoming note on the next stave.

In the example above, the note C is flagged as the next note one can expect after the change of clef.

It’s simply a courtesy to help prepare sightreaders for the music that lies ahead.

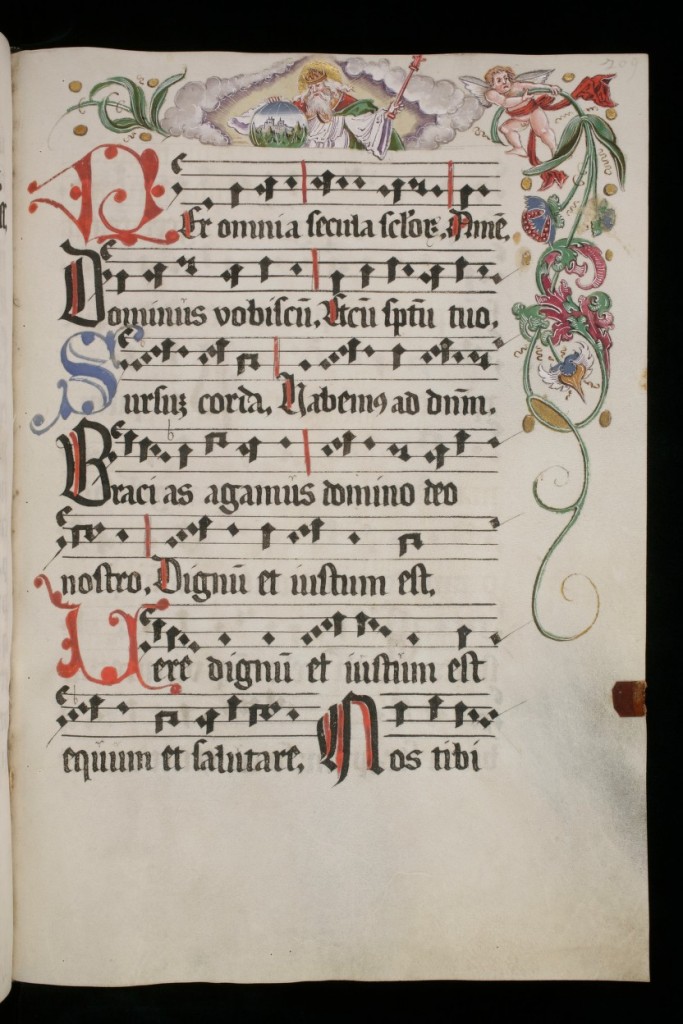

You can see the custos at the end of most of the staves in an illuminated manuscript page from the St. Gall codex below.

Source: St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 357, p. 209 – Missal (https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/csg/0357)

Post feature image source: St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 357, p. 17 – Missal (https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/csg/0357)