Medieval chant neums look very different from today’s music notation… until you get to know them better and discover they’re what made the language of modern sheet music possible. They do however, have their own arcane code, which has been left by the wayside, perhaps in part because few today write anymore with quill pens and also that in typeset music outside of the Catholic Church, note heads have become standardized to a universally accepted roundish shape: (see below eighth note example)

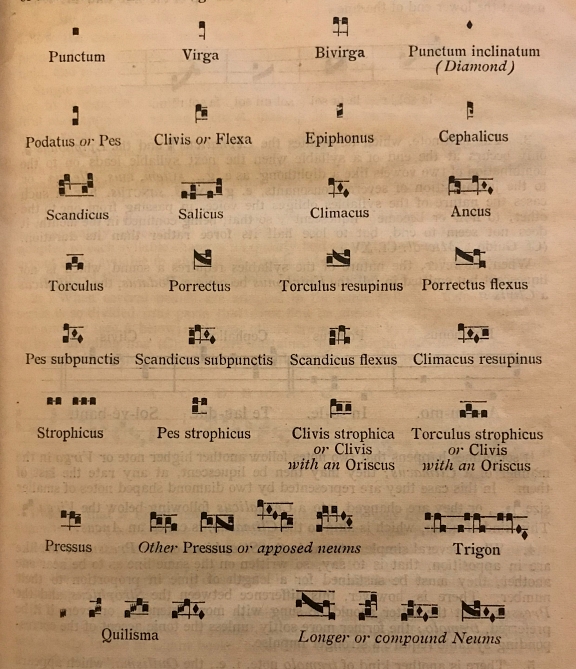

The Roman Catholic Liber Usualis has a helpful chart in its introductory section (the 1934 edition is well over 1900 pages) showing the different types of Gregorian chant neums and their Latin names.

As you can see, the neums near the bottom of the chart are considerably more complex. These are compound neums; a grouping of notes and they have their own rules for reading them correctly. I’ll go into these in a later post. For now, trying to keep things (comparatively!) simple.

The first note at the very top, the punctum, is the note that you’ll see the most often in Gregorian chant and it corresponds with the eighth note above. The next one in the chart that follows, the virga, also corresponds with today’s eighth note.

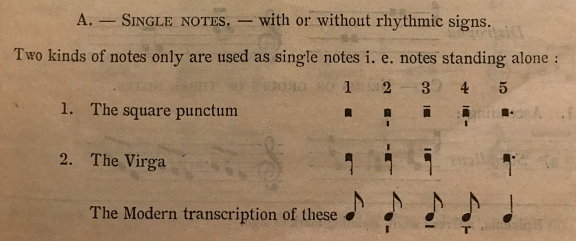

The difference in their shape and meaning is probably best explained by starting with the Liber‘s chart below:

Initially they appear to have the same time values: what we understand today as an eighth. (Gregorian chant does not use metrical values such as 3/4 or 4/4 time in its notation system nor does it use the type of strict measures as in modern music scores).

Notice however, the small dashes above and below the neums. These are called episemas, a Greek word, meaning mark or sign. Their function is to express rhythm or pulse in chant (which does not have a beat as it is understood in today’s popular music).

It’s these small lines that help to give life and breath to Gregorian chant. They are actually, symbols of that essence: breathing in and out as one sings, speaks, chants, the rhythm of speech that found its way and blended into a cappella vocal music, here notated on a page. Over the past several centuries, entire volumes by scholarly monks and academic sacred music researchers on the topic of Gregorian chant rhythm have been written; so much so that there are entirely different schools of thought as to what constituted the pure, the original “Gregorian chant at the time of St. Gregory”.

The Liber goes on to explain the different types of episema on the next page: the vertical one, seen in the second column above, marks the beginning of a beat. The horizontal one, shown in the third column, indicates a slight lengthening of the note. One might say, hold the note just a touch longer or for mild emphasis. In the fourth column, the combined vertical and horizontal episema indicates both the beginning of a rhythmic group and a slight lengthening. This last marks the end of a melodic phrase, with the singing fading away.

In Gregorian chant, dots double the value of the note that precedes it, unlike modern music notation where a dot adds 1/2 the value of a note. For clarification, a dotted eighth note in today’s music would equal an eighth note plus a sixteenth note. In Gregorian chant, that eighth note would be doubled: it would become (theoretically) a quarter note. This is not absolute however, because Gregorian chant does not have a strict beat or rhythm that one would count: “one, two, three, four” and so on as in mensural music. But the neum is held proportionally longer in comparison to surrounding notes.

Knowing this is helpful when reading Gregorian chant and interpreting a vocal music as an instrumental piece. For example, you might not damp a string as quickly or you might let it ring a fraction of a second or two longer before moving on to the next notes. Or you might place a little more pressure on one string than another, letting that note play slightly louder than the others. Just slightly. There are many ways to bring sacred vocal music to life on wire harp!

In my next post, I’ll fill out the mysterious details of the Liber‘s neum chart a little bit more. There’s quite a bit to unpack, so it won’t all happen in one post.

More later!